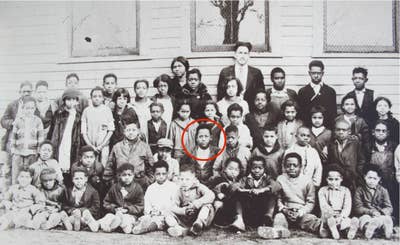

ames Herbert Cameron was born in La Crosse, Wisconsin, in 1914, the second of three children to James Cameron and Vera Carter. His family moved south to Birmingham, Alabama, and lived there until his parents separated in 1928, after which Cameron’s mother moved him and his two sisters to Marion, a modest town of nearly 30,000 where black and white residents attended integrated schools, yet maintained segregated social spaces. (Much of Cameron’s biography and his recollections in this story come from his , A Time of Terror.)

In the summer of 1930, Marion, like much of the country, was experiencing a heat wave that compounded the effects of the Dust Bowl, and scores of people were out of work as the Depression began taking its toll. Cameron, then 16, spent the afternoon of August 6 with his buddies, Tommy Shipp and Abe Smith, pitching horseshoes in a field. It was Smith who convinced Cameron to join him and Shipp later that night to “stick up” unsuspecting couples in a secluded area of town known as “lovers’ lane.” The three teens drove there, armed, and attempted to rob Claude Deeter and Mary Ball, a young white couple. But Cameron recognized Deeter — he regularly shined Deeter’s shoes in town and Deeter tipped well.

Cameron, who had been holding the gun, gave it back to Smith and ran. He heard shots in the distance. Shipp and Smith were arrested shortly after the shooting and allegedly named Cameron as the shooter. Officer Harley Burden, the only black officer on the Marion police force, found Cameron at his mother’s home and took him into custody.

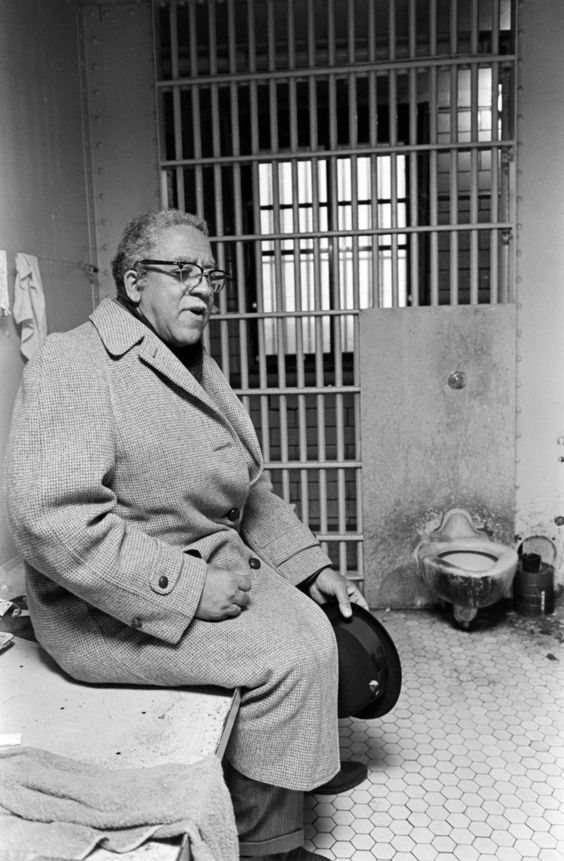

Once Cameron arrived at the Grant County Jail in the early morning hours of August 7, there were already groups of men waiting as word spread of the attack. Deeter was dead by early afternoon, and a police officer hung his bloody shirt in the window of city hall as a visible flag. But Deeter’s death wasn’t the principal outrage that wagged on everyone’s tongues: His companion, Mary Ball, accused Shipp, Smith, and Cameron of rape (an allegation she’d later recant). It was this — the story of Ball’s alleged assault told over and over — that incensed the white residents of Marion and surrounding towns. In his account of the day, A Lynching in the Heartland

For black residents of Marion, such as Katherine “Flossie” Bailey and her husband, Dr. Walter Bailey, it became clear that not only were Shipp, Smith, and Cameron in danger, but the town’s entire black community was too. The Baileys were among Marion’s most prominent black families. Walter was the only black physician in town and Flossie was the president of the state branch of the NAACP. In the aftermath of the arrests, they made every effort to rouse authorities to protect Marion — sending a cable to Gov. Harry Leslie, calling for the National Guard. They phoned the county sheriff, Jacob Campbell, several times demanding that he relocate the three teenagers, as well as seek additional support. Campbell rebuffed their calls and offered his assurances that the boys would be protected. Marion Mayor Jack Edwards, elected only a year prior at the tender age of 27, conveniently left town for “business.” Meanwhile, other black Marion residents fled to neighboring Weaver, a mostly black community, to stay with relatives.

By 9 o’clock on the night of August 7, the mob had swelled to an estimated 15,000. The streets around the courthouse were blocked by crowds and cars. Campbell, who occupied the residence attached to the jail, moved his family to another part of town. “The thing I remember most vividly,” his daughter later recalled, “was seeing so many people, women, standing out there in the crowd with little tiny babies in their arms just hollering, ‘Get in there and get ’em, get in there and get ’em.’”

Mary Ball’s father, Hoot, approached the jail entrance and demanded the keys. “Let us get the niggers,” he told Campbell. “If this was your daughter, you would do the same as I am doing.” From his second-floor cell, Cameron heard Campbell proclaim, “These are my prisoners. Go home!” Yet he was not comforted by the sheriff’s declaration. “Perhaps I imagined it,” he’d later write in his memoir, “but I could not detect a note of sincerity in his voice.”

The mob surged forward, some pummeling the jail with sledgehammers while others forced their way through the garage. When they breached the ground-floor walls, they snatched Tommy Shipp first from his cell. Mary Ball’s sister purportedly watched from atop a car, encouraging the mob to wrap a rope around his neck and lynch him. He was already bruised and beaten when they strung him up on the maple tree at the corner of Third and Adams streets outside of the courthouse, diagonal from the jail. Shipp struggled to free the rope from his neck. The mob lowered him, broke both his arms, and pulled.

“I could see the bloodthirsty crowd come to life the moment Tommy’s body was dragged into view.”

Cameron surveyed the gruesome scene from his cell. “I could see the bloodthirsty crowd come to life the moment Tommy’s body was dragged into view,” he recounted in his memoir. “In a matter of seconds, Tommy was a bloody mass and bore no resemblance to any human being. The mob kept beating him just the same. Even after the long, thick rope had been placed around his neck, fists and clubs still mauled him, and sticks and stones continued to pummel his body.”

After the throng returned for Smith, they beat him with crude weapons, and a man impaled him with a pipe. Smith was dead before they tied the noose around his neck. Cameron heard the gleeful cries once the deed was done. Nauseous and drenched in cold sweat, he knew what was next.

“We want Cameron! We want Cameron!” he heard them chant. When a group of white men forced their way onto the second floor, the black men in his cell block made a fruitless attempt to hide and protect him. “Impulsively, I acted like I was going to give myself up when Big John and another Black man grabbed ahold of me and held me back,” he wrote. “They had become too angry to remember their own fear — if they had any. But they were helpless and powerless to offer any kind of resistance to the mob. They stood with me.”

When the mob threatened to lynch another boy, in jail with his father for hitching trains from the South to look for work, the father pointed to Cameron. “The nightmare I had often heard about happening to other victims of a mob now became my reality,” Cameron wrote. “Brutally faced with death, I understood, fully, what it meant to be a black person in the United States of America.”